The Embodied Steward

A Theory of Nested Emergence and the Technologies of Self-Maintenance

Abstract

This paper argues that conscious awareness shows up when a body starts coordinating itself across too many moving parts for autopilot to hold. Drawing on Levin’s work on developmental bioelectricity, where tissues use electrical patterning to steer growth and repair, Vervaeke’s account of relevance realisation, where cognition keeps selecting what matters for staying in step with the world, and predictive processing (Clark, 2013; Seth, 2021), I develop the Embodied Resonant Emergence (ERE) model. In this model, consciousness is less a thing you possess than a role you enact: you keep forecasting, selecting, and acting so the body stays coherent. That creates a dependency: the body brings the steward into being, and the steward keeps the body from unravelling. I then show how modern environments repeatedly pull this loop off course—keeping threat systems activated (Porges, 2011) and attention captured (Zuboff, 2019)—with predictable consequences for mood, meaning, and social connection. Finally, I outline a recovery pathway through what I call ‘fore-giving’: practising anticipatory care (sleep, movement, nutrition, hygiene, ritual) that lets the predictive machinery re-tune to real bodily needs. The personal is not separate from the political; it is where collective coherence begins.

Introduction: The Body You Were Given and the Steward You Must Become

A Note on Method: This paper develops a theoretical framework through lived experience. I use the first person not to privilege my story, but because embodied knowledge does not travel cleanly as pure propositions (Varela et al., 1991). The Embodied Resonant Emergence (ERE) model first took shape while I was practising, noticing, correcting, and practising again—before I formalised it in theory. What follows is a scholarly personal essay in the phenomenological tradition, where rigour and vulnerability work together rather than cancelling each other out. I cite empirical research where it sharpens the claim, and I draw on direct experience where it names what we cannot yet measure. In an embodied framework, both can carry evidential weight.

Here’s something nobody tells you when you’re young: you don’t simply inhabit your body—you steward it. You emerged when this body became complex enough to need its own caretaker. You are neither your body nor separate from it, but something stranger: you are what happens when a body generates its own guardian.

Think about that for a moment. Your heart has been beating since before you could think. Your lungs have been breathing since before you knew what breath was. Your cells have been coordinating, communicating, maintaining themselves in an ongoing conversation that predates your first memory. The body has been taking care of itself this entire time.

At some point in your development, something shifted. The body became too complex for autopilot alone. It needed something more—a capacity to anticipate, to plan, to respond to a chaotic environment that changes faster than evolution can adapt to. It needed prediction. It needed foresight. It needed you.

This is the central claim of the Embodied Resonant Emergence model: consciousness emerges as the body’s solution to managing its own complexity. You didn’t arrive by accident. You aren’t a ghost haunting meat. You emerged as a steward—generated by the body to maintain the conditions that sustain your existence.

And here’s the catch: when you fail to maintain stewardship, the body begins losing its coherence. As bodily coherence degrades, the steward—that’s you—begins dissolving too. This isn’t metaphor. This describes a mechanism.

The problem is this: practising stewardship demands consistent attention, accurate signal-reading, and anticipatory care. Craig (2002) shows how attending to internal bodily states—interoceptive awareness—enables us to respond before needs become crises. Yet we’re living in environments specifically engineered to disrupt this capacity. Digital capitalism’s profit model depends on capturing and fragmenting our attention (Zuboff, 2019), while modern work structures demand we override bodily signals to maintain productivity (Han, 2015). We are being systematically blocked from performing the role we evolved to fulfill.

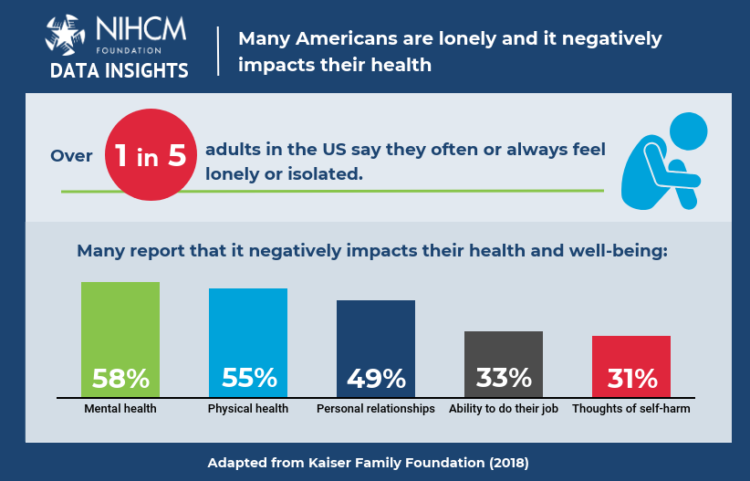

This is the crisis of stewardship. The defining maladies of our time—the loneliness epidemic (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023), soaring anxiety and depression (Twenge et al., 2019), the pervasive sense of meaninglessness (Frankl, 1946/2006)—are symptoms of a systematic disruption in this stewardship loop. We are witnessing what can only be called the Great Un-Grooming: a digital-algorithmic environment that hijacks the body’s prediction machinery, fragments our attention, and starves us of the embodied practices our biology requires.

At the same time, we’re seeing something else: a widespread, intuitive flight back towards “older ways.” The return to ritual and community (Turner, 1969). The new passion for craft, for cooking, for making things with hands (Crawford, 2009). The rediscovery of hygiene not as chore but as practice. This is not nostalgia. This is the organism’s rebellion—an instinctive search for the lost technologies of coherence.

This paper is the manual for that rebellion. It argues that the most profound act of resistance available to us is not political or ideological but embodied: to care for your flesh with the seriousness it deserves. To wash, to move, to sleep, to eat with intention. To remember that you are not just living in a body—you are the body’s way of caring for itself.

Part I: Theoretical Foundation—How Bodies Build Their Own Stewards

1.1 The Pattern That Repeats

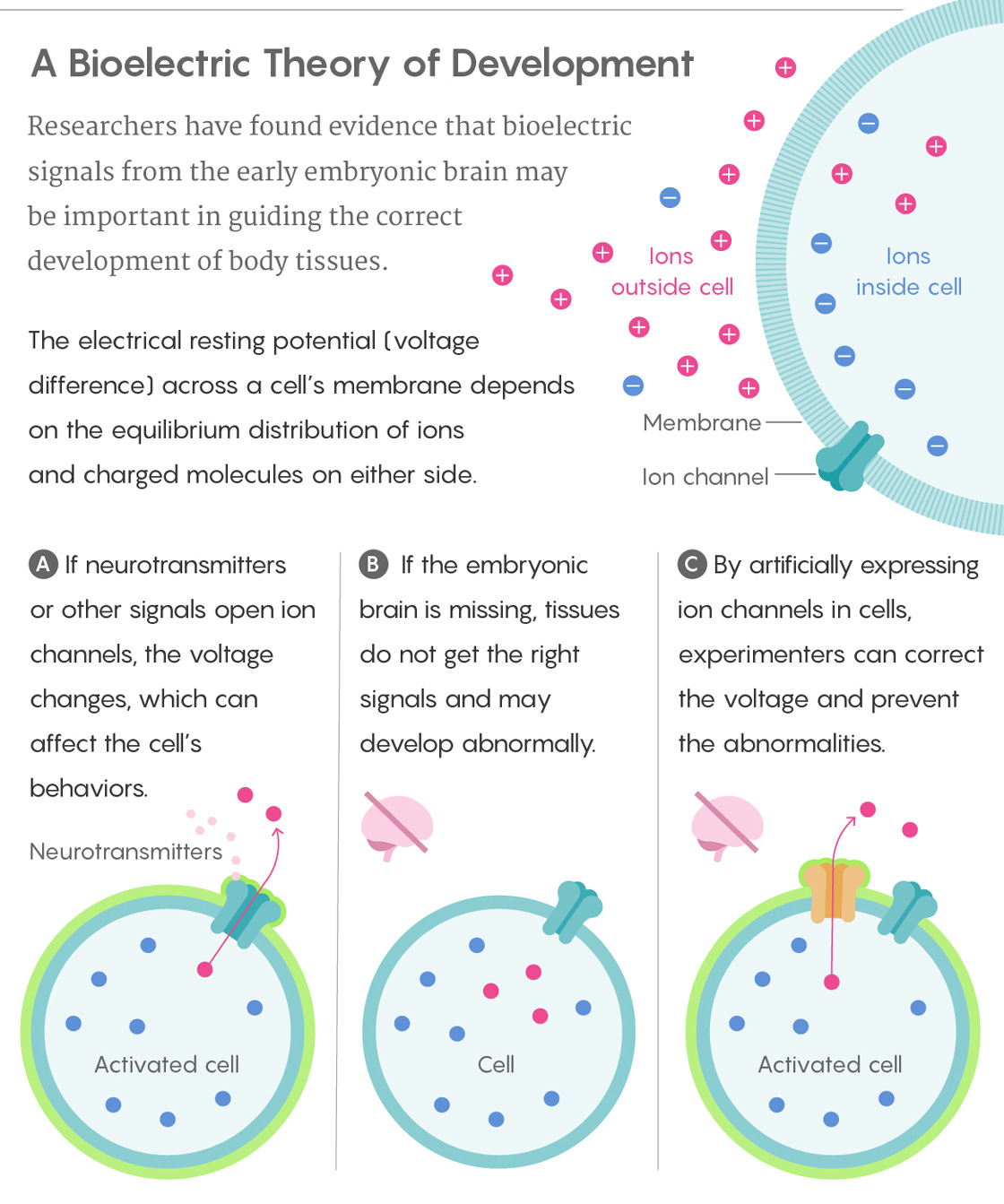

Let me start with what we know. Your body doesn’t assemble itself by reading genes like IKEA instructions and hoping for the best. Genes provide parts and tendencies. But coordinating the build still requires deciding where “here” is, what “missing” looks like, and when “enough” has been achieved. Levin (2021) demonstrates that this coordinating layer isn’t metaphor—it’s physiology.

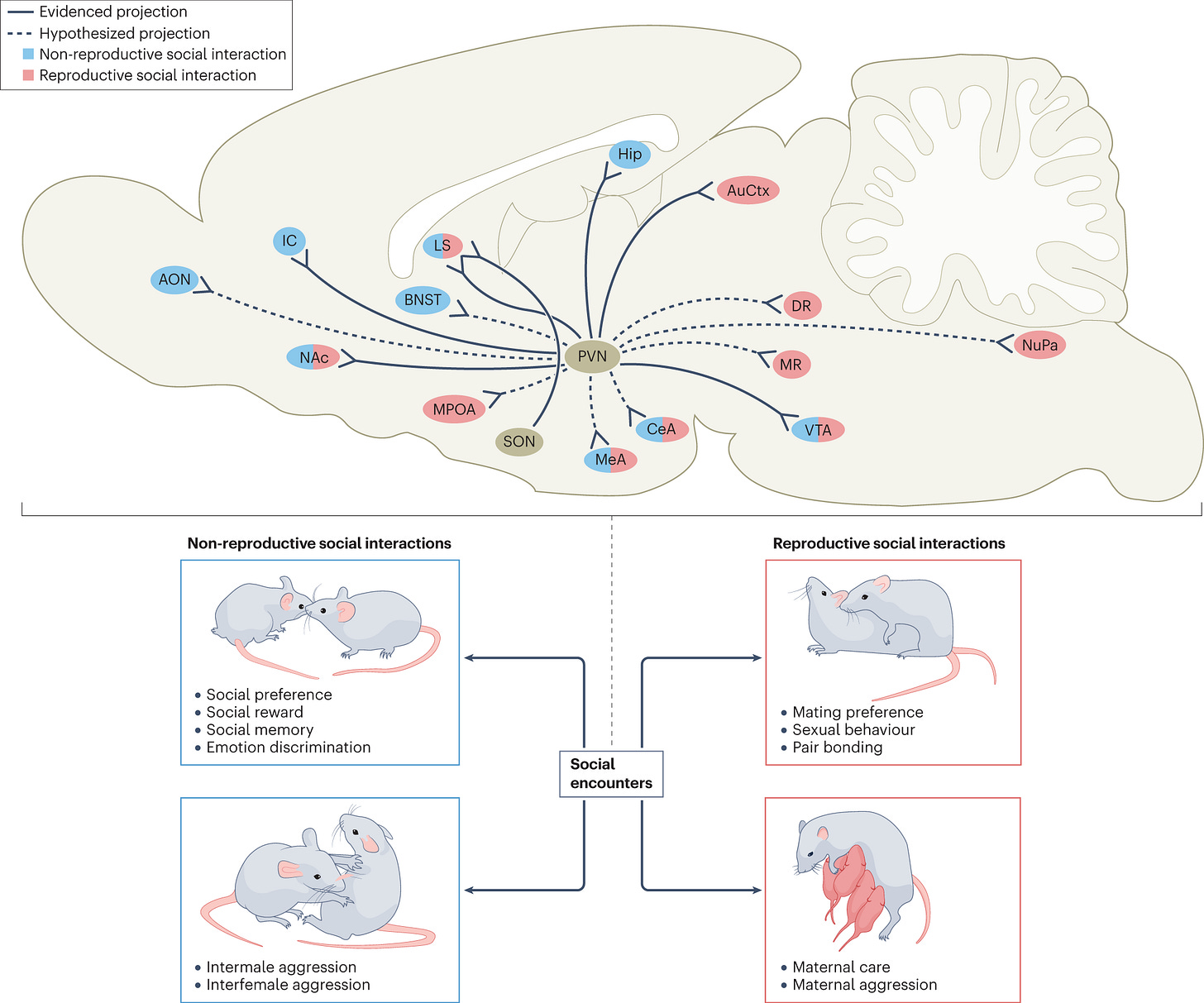

Michael Levin’s work on developmental bioelectricity points to something provocative: at the cellular level, cells don’t merely execute. They negotiate. Levin (2014b) shows how cells communicate through slow bioelectrical signals—patterns of resting membrane voltage (V_mem) produced by ion channels and pumps—sharing these states across tissues through gap junctions, forming networks rather than isolated units.

Here’s the part most people miss: these voltage patterns don’t just correlate with development; in many cases they behave like instructive cues—signals that steer what forms where. Levin (2014a, 2021) demonstrates in review after review how bioelectric gradients function as an informational layer, guiding embryogenesis, enabling regeneration, and even correcting patterning errors.

If that still sounds abstract, watch what happens when researchers “write” new electrical states into tissue.

In Xenopus embryos, a distinct voltage signature demarcates the region that will form the eye. When that voltage state is disrupted, eye development is disrupted. More strikingly, when researchers alter V_mem in cells that were not destined to become eye tissue, they can induce well-formed ectopic eyes—even far from the usual head region. Pai et al. (2012) show this isn’t a gene being “followed blindly”—it’s a collective system responding to a control signal about what kind of structure belongs here.

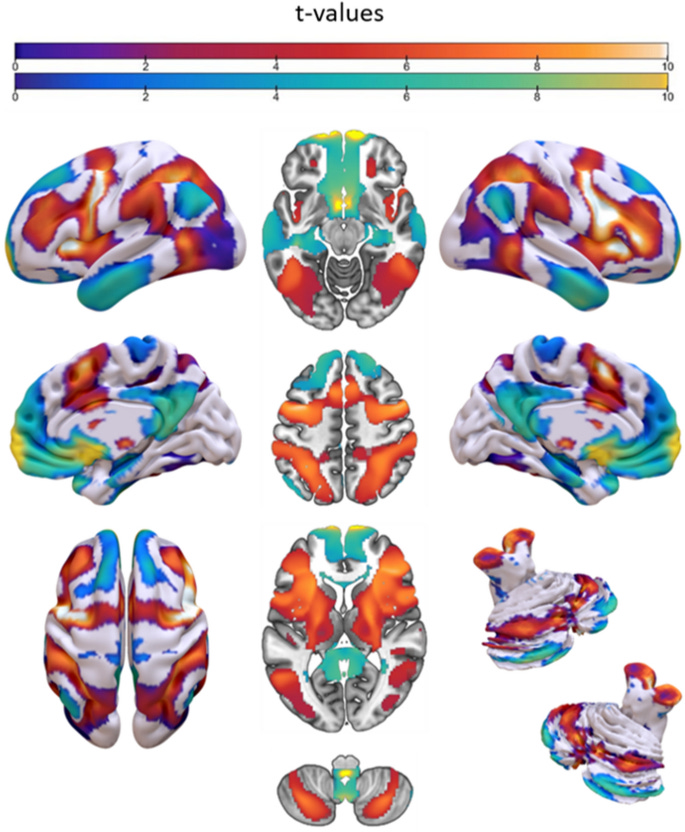

Figure 1. Bioelectric patterns guide embryonic development. Cells communicate through voltage gradients to coordinate tissue formation, demonstrating that biological intelligence emerges from collective electrical signalling rather than genetic instructions alone. (Levin, 2021)

Source: Levin, M. (2021). Bioelectric signaling: Reprogrammable circuits underlying embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer. Cell, 184(8), 1971–1989.

Or take planarian regeneration, where the organism must rebuild proportion, not just mass. Manipulating ion transport (and thus bioelectric state) can change how big the regenerated head becomes and how organs scale—without simply changing how much new tissue is produced. The system isn’t just growing; it’s measuring and correcting. Beane et al. (2013) demonstrate how the system isn’t merely growing tissue—it’s actively measuring and correcting proportions.

Figure 2. Planarian regeneration demonstrates bioelectric pattern memory. When researchers manipulate bioelectric states, the organism rebuilds not just mass but proportion—the system measures and corrects, showing collective intelligence at the cellular level. (Beane et al., 2013)

Source: Beane, W. S., Morokuma, J., Lemire, J. M., & Levin, M. (2013). Bioelectric signaling regulates head and organ size during planarian regeneration. Development, 140(2), 313–322.

So when I say “cells solve problems together,” I mean something specific: cells participate in networks that store and propagate state information, shaping gene expression and behaviour in ways that can’t be reduced to DNA alone. Bioelectric circuits are part of how tissues maintain a kind of “pattern memory”—a shared reference for what the body is trying to build and maintain (Levin, 2014a; Levin, 2021; Mathews & Levin, 2017).

And now the key move—this is where your theme stays intact:

This pattern doesn’t stop at the cellular level. It repeats.

Once cells can coordinate as tissues, tissues coordinate as organs. Once organs can function autonomously, they begin exchanging higher-order signals—creating organ-level coherence. What you’re watching, across scales, is the same basic storyline: local agents acquire a shared language, and a larger intelligence emerges from their coordination (Anderson, 1972).

The logic of emergence doesn’t change across scales—only the medium. What works at the cellular level (distributed intelligence through shared signals) works at the organ level, the system level, and ultimately, at the level of consciousness itself. Watch how this architecture unfolds as we move from cells to organs to systems to consciousness.

1.2 Organs Learn to Speak

Once your organs develop to the point where they can function autonomously—when your heart can beat on its own, when your lungs can breathe, when your liver can filter—something new emerges.

Notice what that implies: your body doesn’t come online all at once. It boots in phases.

Your heart starts early, refusing to wait for the rest of the system to be ready. Männer (2022) describes how it begins moving blood while other capacities remain under construction, setting rhythm before the orchestra is fully seated.

Your lungs arrive later to this conversation, existing long before they can reliably perform their intended work—sustained air-breathing. Nkadi et al. (2009) explain how this “readiness” depends on late-developing biochemical support, especially the surfactant system that keeps tiny air sacs from collapsing.

Your kidneys likewise don’t flip on like a switch. Rosenblum et al. (2017) document how they build their filtering architecture early, then scale capacity across gestation, with functional significance changing as the organism’s broader water-and-waste economy comes online.

So when I say your organs learn to speak, I’m not being cute. Castillo-Armengol et al. (2019) describe what physiology actually looks like once subsystems become capable enough to negotiate with one another: coupled signalling, shared constraints, and feedback control—communication flowing in the only language living systems ever truly use.

Your heart “tells” your lungs how hard it’s working, and your lungs answer by changing the chemistry of your blood. Garcia et al. (2013) demonstrate how these rhythms literally lock together through cardiorespiratory coupling.

Your gut “tells” your brain what’s available—nutrients, stress, safety. Carabotti et al. (2015) document how the brain sends its own messages back through neural and hormonal pathways in what researchers openly call the gut–brain axis.

Your adrenal glands don’t ask for permission. Hillman et al. (2012) show how they broadcast a whole-body state change—mobilising energy, tightening attention, redirecting blood flow—so muscles, heart, and metabolism all shift together.

This isn’t just mechanical signalling—it’s coordination. The organs are doing collectively what the cells did before them: solving the problem of how do we maintain this organism?

And once this starts, something like organ-level coherence appears: a second-order intelligence emerging from the collaboration of first-order intelligences. Your organs, like your cells, are thinking together—meaning they are participating in a shared regulation that no single part can hold alone.

And just as earlier organisation is guided by fields and constraints that shape what cells can become, there is now a nervous system and endocrine system providing the coordination framework for organ-level intelligence—the infrastructure of “speaking” that turns many functions into one life.

1.3 Systems Achieve Coherence

And it doesn’t stop there. The pattern repeats again.

Your cardiovascular system, your digestive system, your immune system—each operates as a network of organs coordinating towards systemic goals. These systems must coordinate with each other continuously. When you eat, your digestive system coordinates with your cardiovascular system, redirecting blood flow. When you exercise, your muscular system coordinates with your respiratory system. When you encounter a threat, your nervous system orchestrates responses cascading across every system simultaneously.

This ongoing process generates systemic coherence—third-order intelligence emerging from second-order coordination. Your body’s systems operate with collective intelligence. They predict, adapt, maintain homeostasis not through rigid programming but through flexible, context-sensitive coordination unfolding moment by moment.

And here’s the crucial point: at each level of organisation, the pattern is the same. Cells coordinate to build organs. Organs coordinate to build systems. Systems coordinate to build... what?

1.4 The Emergence of the Steward

They build you.

When systemic coherence crosses a certain threshold of complexity—when the coordination problem grows too multifaceted for reflexive responses alone—something new must emerge. The body requires a meta-level coordinator. It needs something that can:

• Anticipate threats before they arrive

• Plan responses that span multiple timescales

• Navigate social environments that change faster than genetics can track

• Learn from experience and update predictions accordingly

• Make trade-offs between competing systemic needs

This meta-level coordinator is what we experience as conscious awareness. It is the body’s solution to the problem of operating in an unpredictable environment (Friston, 2010). You are not an accident or an afterthought—you are a necessary emergence when bodies become complex enough to require prediction and foresight.

Defining Coherence: In this paper, coherence is what the body does when it keeps its many processes in step: it synchronises, it couples, it regulates, it recovers. At the cellular scale, coherence shows up when bioelectric potentials synchronise across tissues and keep morphogenesis on track (Levin, 2019). At the organ scale, coherence shows up when organs couple chemical and electrical signals so each adjusts to the others’ demands. At the systemic scale, coherence shows up when nervous and endocrine loops keep restoring homeostasis and renegotiating allostasis. At the conscious scale, coherence shows up when predictive machinery keeps reducing surprise while protecting bodily integrity. Coherence is not stasis; it is dynamic stability. The Greeks had a word for this: tonos—the right tension, the proper tone. Not clamping down into rigidity, not unravelling into chaos, but staying in the living middle where function can hold.

Defining Relevance Realisation: Vervaeke et al. (2017) treats cognition as a continuous act of selection. Out of endlessly many possibilities, you keep making some things matter and letting others fade. Relevance realisation is that ongoing process of making salient what will help the body stay coherent in this context. When it works, thirst makes water stand out, fatigue makes rest rise to the top, and isolation makes connection become urgent. When it is hijacked, notifications win that contest even when sleep is the real requirement. The question is not whether you pay attention, but what your attention keeps serving.

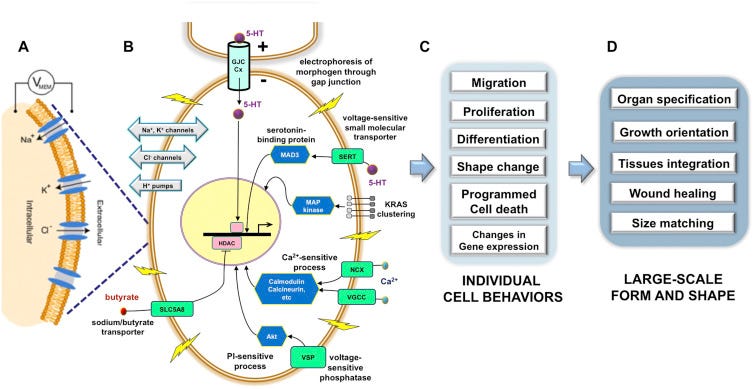

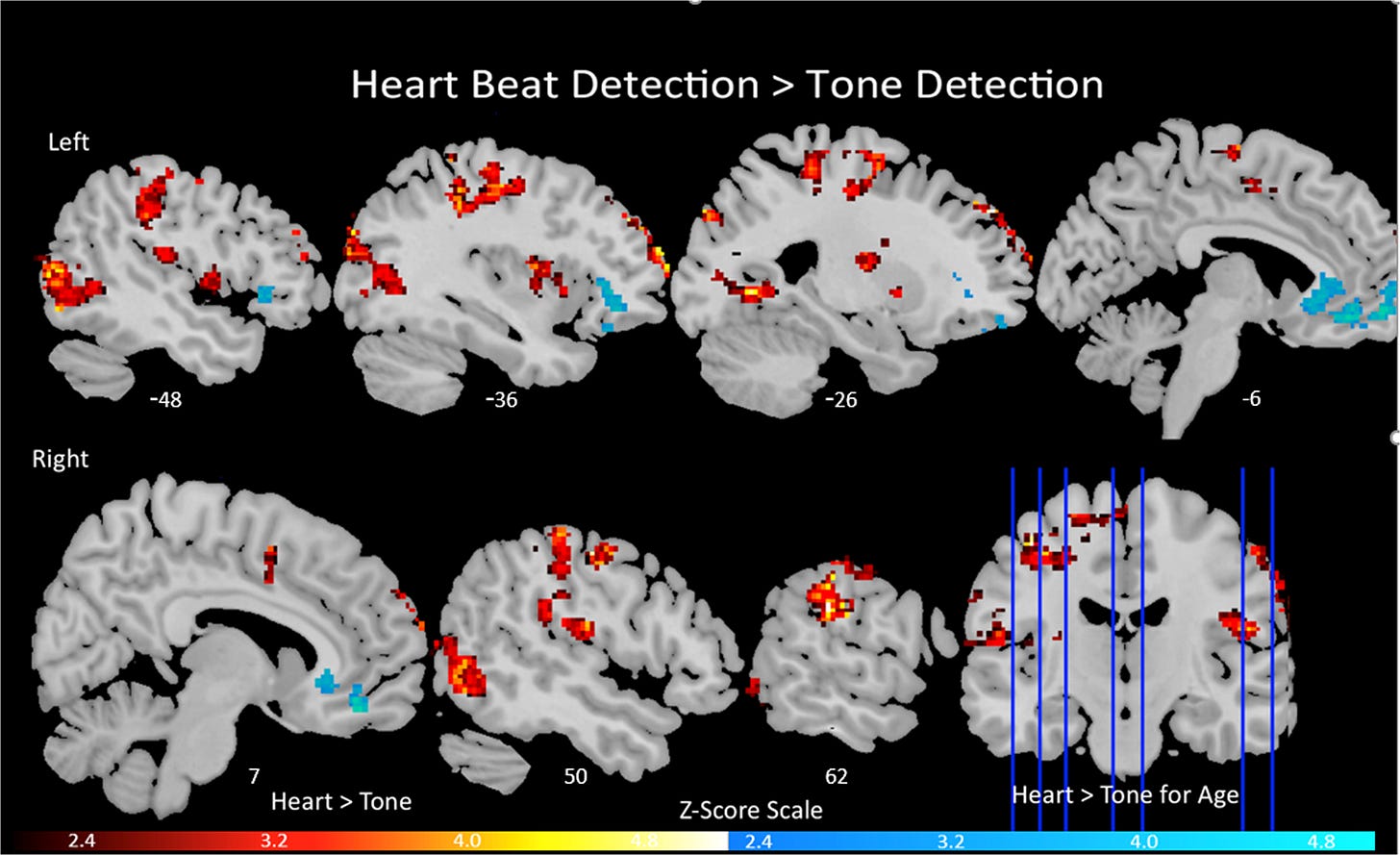

Antonio Damasio’s work traces this emergence beautifully. First comes the proto-self: the body’s continuous mapping of its own internal state. You don’t think about this mapping; it just happens. Your body knows where it is, what position it’s in, whether it’s hungry or tired or in pain. This is interoception—the sense of the body from within.

Figure 3. Functional neuroanatomy of interoception. The insular cortex maps the body’s internal states—hunger, thirst, temperature, pain—creating the felt sense of being embodied that forms the foundation of the proto-self. (Craig, 2002)

Source: Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666.

Then comes the core self: moment-to-moment awareness arising from the continuous stream of bodily changes. When something in the environment affects your body—a loud noise, a touch, a smell—you become aware of the change. This is the feeling of experience happening to you.

Finally comes the autobiographical self: the extended sense of identity that persists across time. This is where you get your sense of “I”—the entity that has a history, makes plans, has preferences, and exists as a continuous being despite the constant flux of experience.

This is nested emergence in action. Each level—proto, core, autobiographical—builds on the previous one. And critically, each level serves the same function the bioelectric field served for cells: coordination towards coherence.

You are the body’s way of coordinating itself across time and context. You are what emerges when the body needs to predict, plan, and respond to complexity.

Table 1. Levels of Nested Emergence in the ERE Model

Note. Each level builds upon the previous, with the same fundamental pattern: local agents coordinate through shared signals to produce emergent intelligence at a higher scale.

Table 2. Damasio’s Three Levels of Self and Their Functions

Note. Based on Damasio (1999). Each level emerges from and builds upon the previous one.

Having established how consciousness emerges from coordinated complexity, we must now examine the peculiar relationship this creates between you and your body. The mechanism generates consequences that feel paradoxical—until you understand the feedback loop at its core.

Part II: The Mechanism—Body and Steward as Co-Dependent Partners

2.1 The Astronaut and the Suit

Now here’s where things get strange. Once you emerge—once consciousness arises from systemic coherence—a peculiar relationship forms. The body generated you, yet now you must maintain the body. A feedback loop circles back on itself. A strange loop, in Douglas Hofstadter’s terms. The effect must maintain its own cause.

Think of it like this: you operate as an astronaut navigating within your suit-body. The suit runs autonomous systems—life support, temperature regulation, pressure management. These function on their own. But the suit cannot navigate terrain by itself, cannot anticipate obstacles, cannot decide where to go or what to do. That falls to you.

Here’s the thing: when the suit fails, you die. When you fail to maintain the suit, the suit fails. The dependency flows both directions.

Each partner depends on the other. The suit generated you, yet you must maintain the suit to continue existing. This ongoing exchange forms symbiotic stewardship—a relationship where each partner continuously maintains conditions for the other’s existence.

The body stewards you by providing the substrate for consciousness. Your neurons fire. Your organs function. Your systems maintain homeostasis. All of this creates the conditions for you to exist as a conscious steward.

In the other direction, you steward the body by doing what it cannot do alone: you predict threats, you plan responses, you make trade-offs, you navigate social complexity. Most crucially, you maintain the external conditions the body needs but cannot ensure for itself. You find food. You seek shelter. You avoid danger. You clean wounds. You rest when tired.

This is not servitude. This is partnership. You are not enslaved to the body—you are what the body becomes when it needs a steward.

2.2 The Body as Pet—A More Intimate Metaphor

The Astronaut/Suit distinction maps the functional relationship—what’s happening mechanically. Now let me illuminate a more intimate dimension of practising stewardship. This second metaphor doesn’t replace the first—it reveals a different aspect of the same relationship. Where Astronaut/Suit reveals structure, what follows reveals feeling.

Relating to your body mirrors how you relate to a pet. You learn its signals. You respond to its needs. You practice tenderness—literally, you learn to “pet” your body.

Anyone who’s cared for a pet knows this relationship. Your dog or cat signals needs—some visible, others you must learn to read. They call for food and water at regular times. They ask for exercise. They need grooming, play, rest, affection. Critically, they depend on you to meet most of these needs. They cannot fulfill them alone.

Pet owners also know how the relationship flows both ways. When you feed them well, walk them regularly, brush their coat, play with them, speak gently to them—something shifts in the exchange. They grow more vibrant, more responsive, more present. Their vitality flows back to you. They offer companionship, joy, a reason to wake each morning. They greet you with genuine happiness.

Your body works the same way.

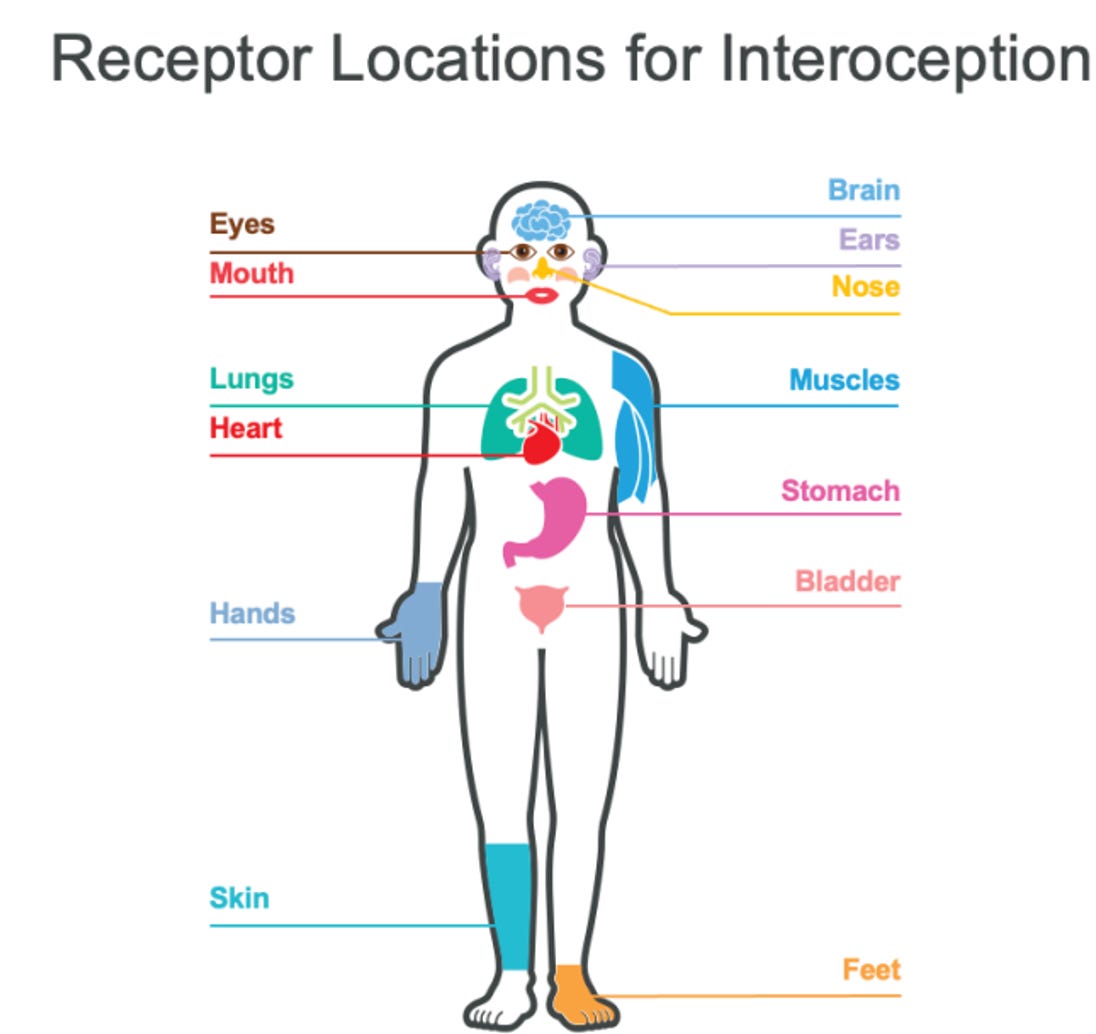

Your body has needs you must learn to read. Hunger, yes—but also the specific hunger for nutrients it’s lacking. Fatigue, yes—but also the need for different types of rest (sleep, stillness, gentle movement). Pain, yes—but also the subtle discomforts that signal “something’s wrong here, pay attention.” Your body is constantly signalling its needs through sensation, and learning to read these signals accurately—what neuroscientists call interoceptive awareness (Craig, 2002)—is foundational to stewardship.

Your body needs regular maintenance. Just like you wouldn’t let your dog go unwashed for weeks, your body needs daily grooming. Shower. Brush teeth. Wash face. These aren’t just social niceties—they’re how you prevent small problems from becoming big ones. The plaque that becomes gum disease (Sheiham, 2005). The uncleaned wound that becomes infected. The unwashed body that becomes a breeding ground for problems. Regular maintenance prevents entropy from accumulating.

Your body needs movement and play. Your dog needs walks not just for bathroom breaks but because moving is what bodies do. They’re designed for it. Same with your body. Sedentary living isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s a violation of what the body is built for (Sedentary Behaviour Research Network, 2012). But here’s the key: it can’t be just any movement. It needs to be movement the body finds engaging, even enjoyable. Play, not punishment. This is why forcing yourself through exercise you hate often fails, while finding movement you actually like tends to stick.

Your body needs affection. This is the part people often miss. You wouldn’t just feed your pet and ignore it emotionally—you’d pet it, speak kindly to it, show it affection. Your body needs this too. Not self-indulgence, but genuine care. The warm shower where you’re not rushing. The meal eaten slowly, tasting it. The gentle stretching that says “thank you for carrying me today.” The body responds to how you treat it (Gendlin, 1978).

Figure 4. Receptor locations for interoception throughout the body. The body signals its needs through sensations distributed across multiple organ systems—learning to read these signals accurately is the foundation of embodied stewardship. (Craig, 2002)

Source: Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666.

Treat it with contempt, and it becomes defensive, tight, painful. Treat it with care, and it opens, relaxes, cooperates.

Your body cannot meet all its needs alone. This is crucial. Just as your pet depends on you to open the food container, to open the door for walks, to schedule the vet appointment—your body depends on you to do what it cannot do for itself. It can digest food but cannot acquire it. It can heal wounds but cannot clean them first. It can sleep but cannot create the conditions for good sleep (dark room, cool temperature, consistent timing). The body generated you specifically to handle these dependencies.

The reciprocity is real. And here’s where the metaphor gets profound: when you care for your body properly, it cares back. Not consciously—your liver isn’t grateful—but functionally. A well-cared-for body provides clearer signals. More energy. Better mood. Sharper thinking. Greater resilience. The body becomes a partner rather than a burden. You feel at home in your flesh rather than trapped in it.

Neglect has predictable consequences. Every pet owner knows what happens when you stop caring properly. The dog becomes listless, unresponsive, develops health problems. Behaviour deteriorates. The joyful companion becomes a source of guilt and stress. The same happens with your body. Neglect it—skip meals, lose sleep, stop moving, ignore hygiene—and it stops cooperating. It becomes heavy, painful, unreliable. The signals get louder and more distressing. Eventually, major systems start failing.

You cannot outsource the relationship. You can pay a dog walker, sure. You can hire a groomer. But the core relationship—the daily presence, the reading of needs, the mutual attunement—that cannot be delegated. Same with your body. You can hire trainers and therapists and doctors, and these can help. But the fundamental stewardship—the daily attending to needs, the consistent maintenance, the affectionate care—that’s yours alone. No one else can feel your body from the inside. No one else can learn its particular rhythms and requirements.

This is why “pet your body” is more than cute wordplay. It’s an instruction manual compressed into a metaphor. Pet your body the way you’d pet a beloved animal. With attention. With gentleness. With consistency. With the understanding that this creature depends on you and will reward your care with vitality.

The body is not your servant. It’s not your enemy. It’s not even really separate from you. It’s your partner—like a pet you’re bonded with, whose well-being directly determines your own. When it suffers, you suffer. When it thrives, you thrive. The relationship is not optional, and it cannot be replaced by any app or algorithm or pill.

You must pet your body. Daily. Gently. Consistently. With genuine care. This is not self-indulgence—it’s the most basic form of self-preservation. Because unlike a pet, if your body fails, there’s no getting another one.

Learn its needs. Meet them consistently. Treat it with affection. And it will carry you through this life with surprising grace.

The Astronaut/Suit distinction explains what’s happening functionally. The Pet metaphor explains how it feels experientially. Use whichever resonates more deeply for you, but understand they’re describing the same underlying dynamic: a partnership where both parties need each other to survive.

2.3 Predictive Processing: The Mechanism of Stewardship

How does this stewardship actually work? The answer comes from predictive processing theory, developed by Karl Friston, Andy Clark, Anil Seth, and others.

Your brain is not a passive receiver of information. It’s a prediction machine. At every moment, your brain is generating predictions about what should be happening—in your body, in your environment, in your social world. These predictions are based on past experience and serve a single purpose: to minimise surprise.

Why minimise surprise? Because surprise means something unexpected has happened. And in evolutionary terms, unexpected things were often dangerous.

Figure 5. The brain as a prediction machine. Predictive processing theory shows how consciousness emerges from the body’s continuous effort to minimise surprise by generating and updating predictions about internal and external states. (Clark, 2013)

Source: Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204.

A rustle in the bushes that you didn’t predict might be a predator. A pain in your chest that you can’t explain might be a heart attack. Surprise signals prediction error—a mismatch between what your brain expected and what actually happened.

The Causal Sequence:

To clarify the causal relationship and avoid circularity:

1. Bodily coherence enables consciousness (bottom-up): Organised bioelectric/neural activity → systemic integration → emergence of predictive processing capacity. Without coherent substrate, no steward emerges.

2. Consciousness maintains conditions for its own substrate (top-down): Predictive machinery → relevance realisation → behavioural responses → maintenance of bodily coherence. The steward acts to preserve the conditions that generated it.

3. Feedback loop, not circle: This creates a reinforcing cycle rather than circular logic. Good stewardship → better coherence → more effective prediction → better stewardship. Conversely: poor stewardship → degraded coherence → impaired prediction → worse stewardship. The directionality matters: initial coherence is a prerequisite for emergence, but once emerged, the steward becomes constitutively necessary for maintaining that coherence (Pezzulo et al., 2015).

This is where stewardship happens. When your brain detects prediction error, it has two options:

1. Update the prediction (learn that the world is different than you thought/respect reality)

2. Change the world (act to make reality match your prediction/update reality)

Option 2 is stewardship. When your body predicts it needs water and detects dehydration (prediction error), you don’t update your model to accept being dehydrated. You act—you find water, you drink. You change reality to match the prediction that your body should be hydrated.

This is John Vervaeke’s relevance realisation in action—finding the point in each moment. At every moment, you’re faced with infinite possible things you could attend to, infinite actions you could take. Relevance realisation is your capacity to grasp what matters for maintaining systemic coherence. What’s salient for keeping the body functioning? What actions will minimise prediction error and maintain coherence?

When you’re thirsty, water becomes relevant. When you’re tired, rest becomes relevant. When you’re cold, warmth becomes relevant. This isn’t conscious deliberation—it’s your predictive machinery determining what matters for maintaining the body’s coherence.

When relevance realisation works well, you hit the point—you respond appropriately to actual needs. When it’s hijacked, you miss the point—you scroll when you need sleep, you eat when you need connection, you work when you need rest. Missing the point always has consequences. Sometimes they’re immediate (exhaustion, illness). Often they’re delayed (chronic disease, relationship breakdown, meaninglessness). The art of stewardship is learning to stay with the point as it moves—recognising that your needs shift moment to moment, day to day, season to season.

And this is why consciousness evolved: to predict and respond to challenges the body cannot handle reflexively. You are the body’s forward-looking capacity. You are its way of anticipating chaos and responding proactively before damage occurs.

2.4 Why You Cannot Turn It Off

This explains something important: why you cannot turn consciousness off. Why you cannot simply stop being aware, stop caring, stop predicting.

Because stewardship is not optional. It’s not a feature you can disable. It’s inherent in your nature as an emergent coordinator. The body generated you specifically to perform this function. Trying to stop stewarding is like trying to convince your heart to stop beating—it’s not under voluntary control at that level.

Even when you sleep, the predictive machinery continues. Dreams are your brain running simulations, testing predictions, consolidating learning. Even in rest, stewardship continues.

This is why neglect feels so wrong. Why depression—the loss of capacity to care—is experienced as a kind of death (Raison & Miller, 2013). When the steward stops stewarding, the feedback loop breaks. The body begins to lose coherence. And as coherence degrades, the steward itself begins to dissolve.

You are not separate from the body, trying to control it from outside. You are the body’s capacity to care for itself. When that capacity fails, both body and steward suffer.

Part III: Distinguishing Needs—The Body and The Steward

3.1 Two Kinds of Hunger

Notice the subtle but critical distinction: the body and the steward, while inseparable, have different needs. Failing to distinguish between them is one of the primary mechanisms through which modern environments disrupt stewardship.

The Body’s Needs (Substrate Maintenance):

Your body has mechanical requirements for maintaining its physical integrity:

• Nutrients (macros and micros)

• Hydration

• Sleep and rest

• Movement and physical challenge

• Temperature regulation

• Waste elimination

• Healing and repair time

The body signals these needs through interoception—the sense of the body from within (Craig, 2002). Hunger signals nutrient deficit. Fatigue signals need for rest. Discomfort signals need for movement or position change. These are mechanical messages about the substrate’s state.

The Steward’s Needs (Coherence Maintenance):

Once consciousness emerges, it has its own maintenance requirements that cannot be reduced to bodily needs. Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) identifies three basic psychological needs that are universal to human well-being:

• Autonomy (the experience of volition and self-determination)

• Competence (the feeling of effectiveness and mastery)

• Relatedness (the sense of connection and belonging)

When these psychological needs go unmet, the steward experiences distress—but this distress manifests differently than physical hunger. You might feel:

• Meaninglessness (lack of purpose or engagement)

• Boredom (need for novelty, learning, or challenge)

• Loneliness (need for authentic connection)

• Emptiness (lack of beauty, transcendence, or aesthetic experience)

• Powerlessness (lack of agency or control)

These are experiential needs. The steward signals them through emotions rather than physical sensations. We might call this the spirit or mood of the self—not in supernatural terms, but as the felt quality of your embodied experience. When bodily coherence is maintained and steward needs are met, the spirit is one of vitality, possibility, engagement. You feel alive. When coherence degrades and needs go unmet, the spirit becomes heavy, stuck, despairing. This isn’t metaphor—it’s the phenomenological signature of the body-steward relationship functioning or failing.

The Critical Distinction: Physical Hunger vs. Emotional Hunger

Research on emotional eating provides clear evidence that these two types of needs are distinct and require different responses (Macht, 2008; Reichenberger et al., 2018).

Table 3. Distinguishing Physical Hunger from Emotional Hunger

Note. Based on research by Macht (2008), Reichenberger et al. (2018), and Albers (2019).

The distinction is not just academic. Studies show that when people cannot differentiate between physical and emotional hunger, they are more likely to overeat, develop disordered eating patterns, and fail to address the actual needs driving their behaviour (Tomova et al., 2020).

3.2 The Chocolate Example: When Conflation Creates Pathology

Imagine you’re at your desk mid-afternoon. You feel... something. A pull. A need. “I’m hungry,” you think.

Let’s look more carefully:

Body says: “I need nutrients” (it’s been 3 hours since lunch, blood sugar is dropping)

Steward says: “I’m bored/stressed/lonely” (the work is tedious, you’re anxious about a deadline, you feel isolated)

Confused response: You eat a box of chocolates. The sugar provides a temporary dopamine hit that addresses the steward’s need for pleasure. But it doesn’t provide the nutrients the body needs. And it doesn’t address the actual emotional need (meaning, connection, autonomy). Result: the body remains under-nourished, the steward remains empty, and you’ve added guilt to the emotional mix.

Skilled response:

1. Pause and distinguish: “Is my stomach empty? When did I last eat? Or am I feeling an emotion?”

2. If body-hungry: Eat vegetables and protein—what the body actually needs

3. If steward-empty: Address the emotional need appropriately (take a walk, call a friend, do something meaningful)

4. If both: Do both, in that order. Maybe honour the steward’s need for pleasure with one piece of chocolate after addressing the body’s nutrient needs

This isn’t about discipline or willpower. It’s about accurate signal interpretation.

Table 4. The Chocolate Example: Confused vs. Skilled Response to Mixed Signals

Note. The key skill is pausing to distinguish which system is signalling before responding.

When you can distinguish body-needs from steward-needs, you can respond appropriately to each.

Why Conflation Happens: The Evolutionary Mismatch

In evolutionary context, this conflation made sense. For most of human history:

• Food scarcity meant “hungry” and “empty” happened together (caloric deficit and emotional distress from hunger)

• Eating met both needs simultaneously (nutrients + social bonding through shared meals + meaning through successful foraging/hunting)

• The environment didn’t offer infinite hyper-palatable foods designed to hijack reward systems

Modern environments break this elegant system:

1. Engineered foods exploit the confusion. Hyper-palatable foods (high sugar, salt, fat combinations that don’t exist in nature) trigger steward’s pleasure centres without meeting body’s nutrient needs. They’re designed to maximise dopamine while minimising satiation—keeping you coming back.

2. Emotional needs systematically go unmet. Modern life frustrates psychological needs (autonomy crushed by surveillance, competence undermined by precarity, relatedness starved by isolation). The steward is constantly seeking relief.

3. Food becomes the default solution. Food is always available, socially acceptable, and provides immediate (if temporary) relief. It’s easier to eat than to address meaninglessness, easier to snack than to deal with loneliness.

4. Interoceptive accuracy degrades. When you repeatedly use food to address emotional needs, you lose the ability to distinguish “body hungry” from “steward empty.” It all just feels like “I need something.”

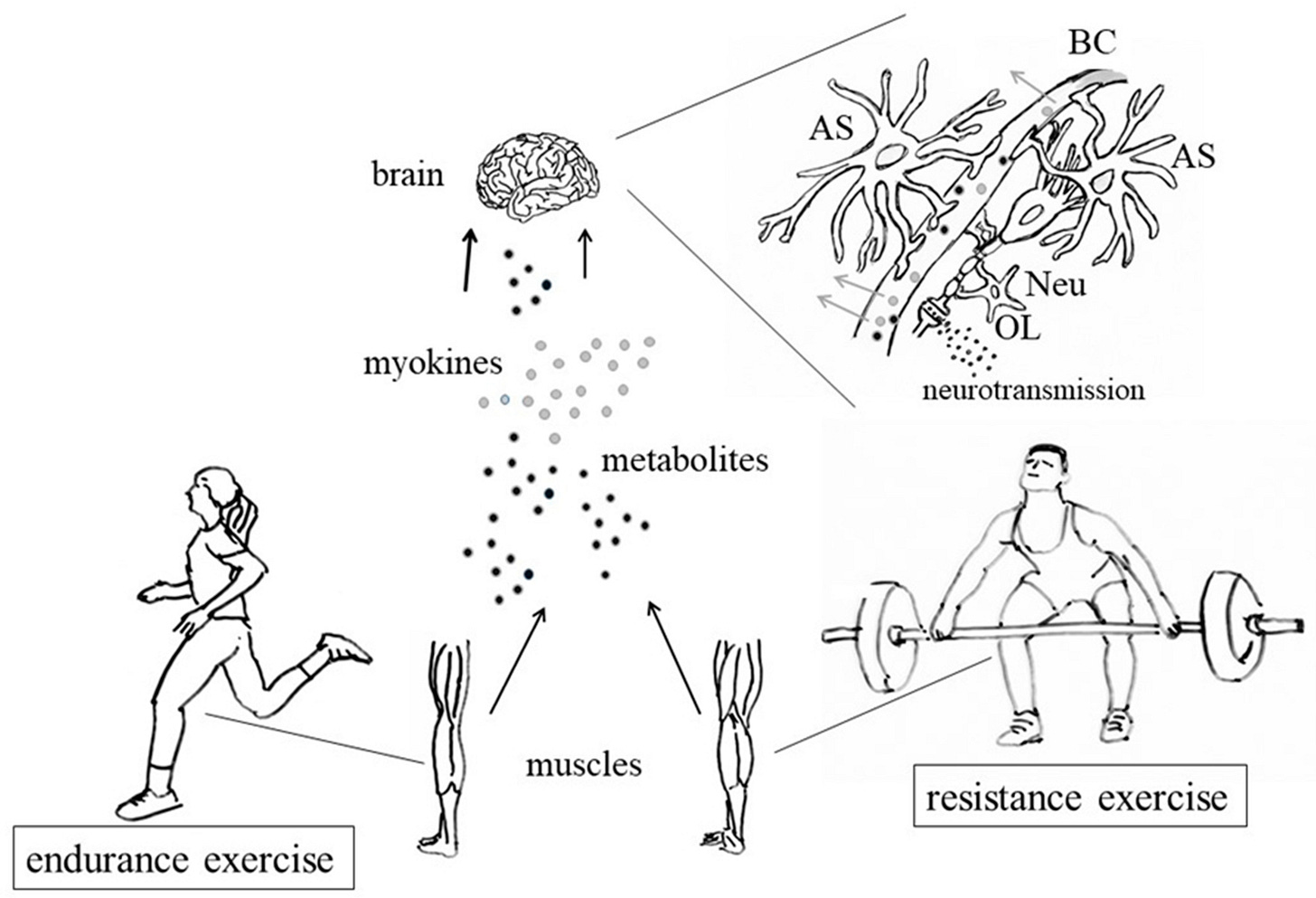

Figure 6. Exercise-mediated effects on brain functions. Both endurance and resistance exercise allow muscle synthesis and release of myokines (e.g., BDNF) and metabolites (such as lactate) into circulation. These molecules cross the blood-brain barrier and affect neurons and glial cells, modifying neurotransmission in different brain regions. (Di Liegro et al., 2019)

Source: Di Liegro, C. M., Schiera, G., Proia, P., & Di Liegro, I. (2019). Physical activity and brain health. Genes, 10(9), 720. . CC BY 4.0.

Table 5. Distinguishing Body and Steward Needs: A Comprehensive Comparison

Note. Both types of needs must be addressed appropriately; conflating them leads to pathological patterns.

3.3 Listening to Your Body: The Practice of Accurate Signal Reading

The body doesn’t speak English. It speaks in sensations—hunger, fatigue, tension, ease. But these sensations are dynamic, shifting in real-time, like trying to photograph a carnival. By the time you’ve named the feeling, it’s already changed.

This is why interoception is difficult. You must learn to stay with moving felt experience rather than freezing it into fixed categories. “I’m tired” might be true, but what kind of tired? Physical exhaustion? Boredom? Emotional depletion? Existential weariness? Each requires different care.

The Practice:

When you notice discomfort, don’t rush to name it. Stay with the sensation. Feel how it shifts. Notice what contexts amplify or diminish it. Ask yourself:

If someone offered me a plate of vegetables and grilled chicken right now, would I eat it?

• If yes: Your body is hungry. Feed it appropriately.

• If no—you only want cookies/chips/chocolate: Your steward is seeking something (pleasure, comfort, distraction). What’s the emotional need? Can you address it directly instead of through consumption?

• If both: You’re both body-hungry and steward-empty. Address body first (you can’t think clearly when blood sugar is low), then tend to the emotional need.

The felt experience will reveal its meaning if you give it space. This is the art of listening to a body that cannot speak in words. It’s learning to hear not just what is being signalled, but why it’s being signalled now.

3.4 Implications for Pathology

This framework explains patterns that otherwise seem contradictory:

Binge eating: Trying to meet emotional needs (usually autonomy or relatedness deficits) through consumption. The body gets overfed, but the steward remains starving—so the behaviour repeats.

Restrictive eating/orthorexia: Trying to meet emotional needs (control, moral purity, identity) through perfectionist nutrition. The body’s nutrient needs might be met, but the steward’s needs for authentic connection, spontaneity, and pleasure are sacrificed. The “care” becomes compulsive because it’s solving the wrong problem.

Yo-yo dieting: Swinging between restriction (steward seeking control) and bingeing (steward seeking pleasure/relief), never addressing the actual emotional needs driving both behaviours.

Addiction patterns: Whether food, substances, or digital stimulation—using consumption to address experiential emptiness. The body’s needs get disrupted, the steward’s needs remain unmet, and the feedback loop degrades.

Why “Self-Care” Often Fails

Modern “self-care” industry often conflates these needs in unhelpful ways. It sells:

• Bubble baths and face masks (addressing neither body’s hygiene needs nor steward’s meaning needs adequately)

• “Treating yourself” to dessert (using body-consumption to address steward-emptiness)

• Expensive wellness products (offering steward sense of control/identity through body consumption)

Real stewardship requires meeting both sets of needs appropriately:

For the body: Basic hygiene, adequate sleep, whole foods, regular movement, hydration

For the steward: Meaningful work, authentic connection, autonomy, competence, beauty, purpose

When body needs are met, the steward has resources to pursue meaning. When steward needs are met, the steward has motivation to care for the body. They’re mutually reinforcing—but only when distinguished and addressed appropriately.

Understanding the distinction between body and steward needs reveals only part of the picture. The stewardship loop can fragment in another way—when the steward itself splinters into multiple competing selves, each claiming to speak for “you.” We must now examine what happens when the village within loses its coherence.

Part IV: The Village Within—When the Steward Fragments

4.1 The Multiplicity of Self

The body-steward relationship is not the only coordination problem. The steward itself is not monolithic—it’s what we might call a “village of selves.”

Think of it this way: when you’re driving, you become “driver-you”—sensitive to road signs, traffic, the mechanics of steering. When you’re cooking, you become “cook-you”—attuned to temperatures, timing, flavours. When you’re parenting, “parent-you” emerges—patient, protective, pedagogical. These aren’t masks you wear; they’re genuine aspects of who you are, each optimised for different contexts.

The coordinating self is the part of you reading these words right now, deciding which version of yourself to bring forth for which situation. This is relevance realisation at the level of identity: Which version of myself is most salient for this context?

When the system works well, you browse your collection of selves like selecting an outfit from a wardrobe. The context tells you what’s needed. You arrive at the car, check for keys, grab the driver-self, and off you go. Seamless. Transparent. Flow.

When the system breaks—when you’re stressed, traumatised, or chronically disrupted—something insidious happens: you start creating counterfeit selves.

4.2 The Counterfeit Problem

A counterfeit self is a version of yourself you construct not because it’s authentic, but because it’s impressive or safe. It’s the resume-tailored version you present at job interviews. The polished version you perform at parties where you don’t quite belong. The “I’m fine” you wear when you’re falling apart inside.

Creating counterfeits isn’t inherently pathological—sometimes survival demands it. The problem is what happens next.

Because counterfeits are effortful to maintain (they’re not grounded in your actual capacities or preferences), they’re unstable. Under stress or time pressure, you default back to the less impressive authentic version—but now your audience is confused. “What happened? You were so [confident/articulate/together] last time.” And you’re confused too, because both versions feel like “you.”

The closet becomes cluttered. Duplicates proliferate. You lose track of which selves are authentic and which are performance. And when you need to respond quickly—when the body signals a need or the environment demands action—you grab the wrong self.

This is steward-level dissonance. The body’s signals might be clear, but if the steward is fragmented across counterfeits, it can’t coordinate an appropriate response. You know you’re hungry, but “cook-you” is buried under three counterfeit versions of “professional-you”. You know you need rest, but “rest-capable-you” has been sidelined by “productive-you”, “impressive-you”, and “can’t-show-weakness-you”.

When the counterfeits take over, something gets buried—what we might call your divine self. Not divine in supernatural terms, but divine as in most authentic, most coherent, most aligned with what you actually are. It’s the version of you that exists when you’re safe, seen, cared for. The you that your loved ones glimpse in your best moments.

The tragedy is: when you’re stuck in counterfeit modes, even you cannot see your divine self. It’s locked on the inside. And the less you see it, the less you can care for it. You’re maintaining a performance instead of stewarding an actual person.

Here’s why this matters for embodied stewardship: when you’re operating from a counterfeit self, you cannot accurately read your body’s signals. The body sends hunger cues, but “professional-you” interprets them as weakness. The body signals fatigue, but “productive-you” sees rest as failure. The body asks for connection, but “independent-you” refuses to appear needy. Counterfeit selves don’t just fragment identity—they fracture the stewardship loop itself. You cannot care for a body when you’re pretending to be someone who doesn’t need care (Winnicott, 1960). The body knows the difference between authentic presence and performance. And when it detects performance, it cannot relax into the trust required for coherent signalling.

4.3 The Curation Solution: Vacation as Maintenance

The etymology of “vacation” comes from the Latin vacare—to empty out. This is stewardship of the steward itself. You must periodically empty your closet of selves, examine each one, and ask:

• Is this authentic, or did I create this to impress someone?

• Does this self still serve me, or have I outgrown them?

• Which selves have I been neglecting that I need to cultivate?

This isn’t self-improvement in the conventional sense. It’s identity hygiene—maintaining the coherence of the steward just as you maintain the coherence of the body.

When I was younger, discovering a less-impressive self felt like failure. I’d double down, create more counterfeits, try harder to be the impressive version. Older me has learned to be empathetic to my selves. They’re all trying to help. The less impressive ones just need cultivation, not replacement.

4.4 Cultivation Through Four Ways of Knowing

How do you cultivate an authentic self from a less impressive starting point? Through what John Vervaeke calls the four ways of knowing:

1. Propositional knowing (facts): Learn about the domain. Read, watch, study.

2. Procedural knowing (practice): Do the thing. Acquire skills through repetition.

3. Perspectival knowing (community): Join others who take this seriously. Share experiences.

4. Participatory knowing (identity): Make it part of your life. Identify as this.

Table 6. Vervaeke’s Four Ways of Knowing Applied to Self-Cultivation

Note. Based on Vervaeke et al. (2017). Steps cannot be skipped; each builds on the previous.

This is how driver-me became cyclist-me. How cook-me became chef-me. Each cultivation takes time, but the result is a self you can trust—one that shows up reliably, authentically, coherently.

Notice the pattern: you cannot skip steps. You cannot go directly from reading about sleep to identifying as someone who sleeps well. You must practice. You must do it with others. You must let it become part of who you are.

4.5 Scaling the Curation

The challenge is: you have limited time and many selves to tend. Some are currently relevant (work-self, parent-self, partner-self). Others are dormant but important (creative-self, playful-self, spiritual-self). Still others have become obsolete (the people-pleasing self you needed in high school but no longer serves you).

Effective stewardship means prioritising which selves to cultivate now and which to pause. It means accepting that you’re a lifelong work-in-progress. It means recognising that showing up authentically—even as a less polished version—is better than showing up as a counterfeit.

The body can tell. When you’re operating from a counterfeit self, your body knows. The tension. The vigilance. The subtle strain of maintaining a performance. This is low-grade allostatic load—stress that doesn’t resolve because you’re literally at war with yourself.

Authenticity isn’t a luxury. It’s a substrate requirement. The body can only relax into coherence when the steward is coherent. And the steward can only be coherent when the village of selves is organised, with counterfeits cleared out and authentic versions tended.

The fragmentation of self into counterfeit identities doesn’t happen in a vacuum. While individual psychology plays a role, the epidemic scale of this phenomenon points to something systemic. We must now examine the environmental forces that actively engineer this dissonance.

Part V: The Diagnosis—How Modern Environments Disrupt Stewardship

5.1 The Dissonance Engine

Now we arrive at the diagnosis. When stewardship forms the core function of consciousness, and when stewardship depends on predictive processing and relevance realisation, what happens when these systems get systematically hijacked?

This describes what’s happening now. We’re living inside what can only be called a Dissonance Engine—systems engineered to create prediction errors your body cannot resolve, trapping you in chronic arousal that degrades coherence. Zuboff (2019) documents how these operate as intentional architectures optimised for attention capture, while Fogg (2003) reveals their behavioural modification foundations.

I don’t mean “designed” in the sense of conspiracy. I mean emergent design—the natural consequence of systems optimising for profit without regard for human coherence. Shoshana Zuboff calls it surveillance capitalism. The business model is simple: capture attention, predict behaviour, sell predictions. But the mechanism by which this works is hijacking relevance realisation.

Your brain’s predictive machinery evolved to track what matters for bodily coherence: threats, opportunities, social bonds, resources. But social media platforms exploit this machinery. They’ve discovered that prediction error itself—surprise, novelty, outrage—drives engagement. So they optimise for maximum prediction error. They create an environment of constant surprise.

This does something devastating: it breaks the connection between relevance realisation and bodily needs. Your brain is constantly signalling “this is important!” but what it’s tracking has no relationship to actual bodily coherence. You’re not finding food or avoiding predators—you’re scrolling through feeds, chasing notifications, responding to manufactured urgency. You’re constantly missing the point—scrolling when you need sleep, checking feeds when you need connection, consuming content when you need meaning.

5.2 The Biology of Chronic Disruption

Robert Sapolsky’s work on stress provides the physiological mechanism. Your body’s stress response evolved for acute threats: the predator in the bushes, the rival threatening violence. In these contexts, the stress response is adaptive—cortisol floods your system, redirecting resources towards immediate survival.

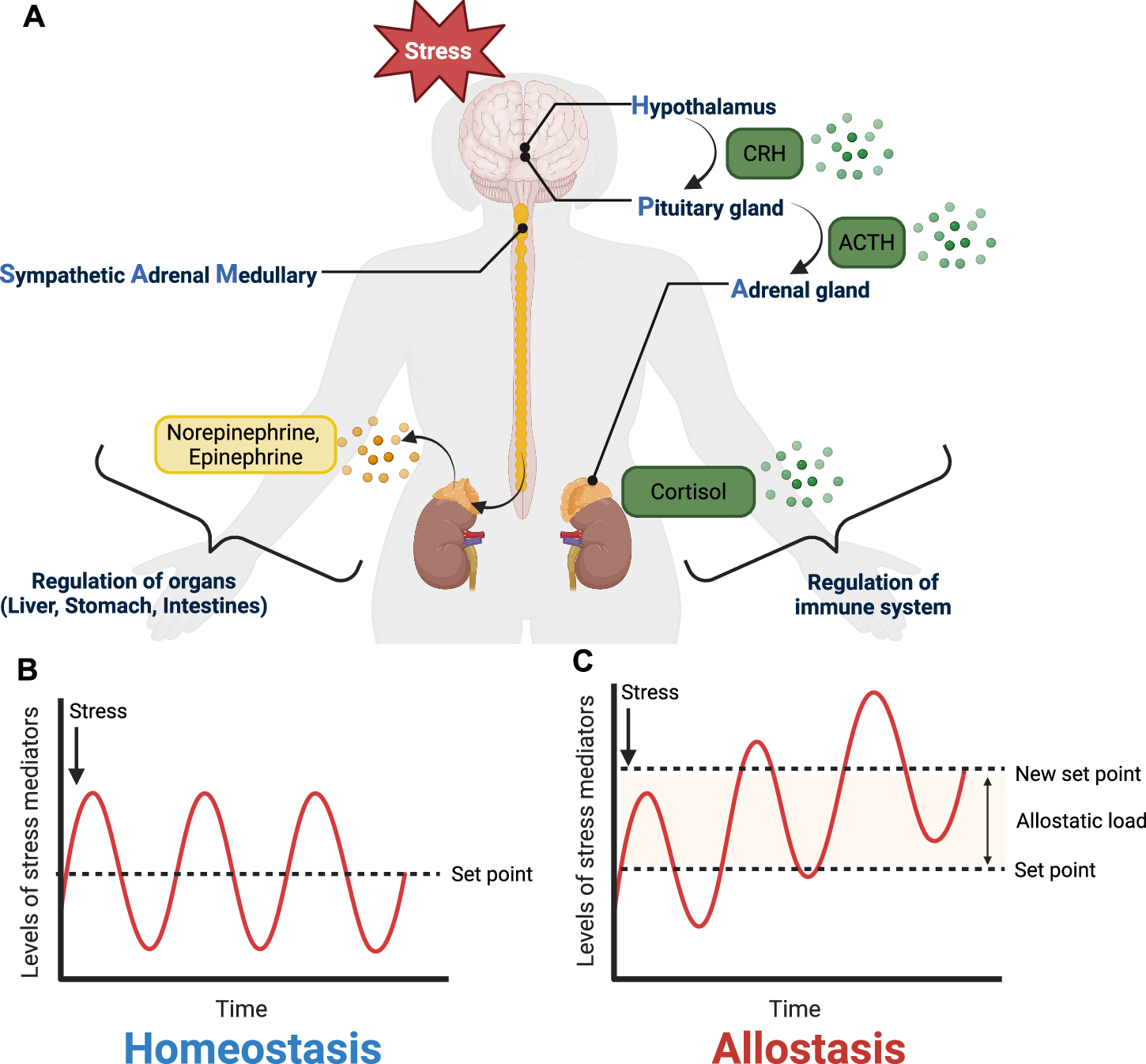

Chronic stress—stress that never resolves—is pathological. It creates what’s called allostatic load: the cumulative wear and tear of constant physiological activation. Your immune system is suppressed. Your cardiovascular system is strained. Your digestive system is disrupted. Your sleep is fragmented. This is the body losing coherence under sustained pressure.

Figure 7. Allostatic load and its effects on the brain. Chronic stress creates cumulative wear and tear through constant physiological activation, degrading coherence across body systems and impairing the steward’s capacity to maintain the body. (Peters et al., 2017)

Source: Peters, A., McEwen, B. S., & Friston, K. (2017). Uncertainty and stress: Why it causes diseases and how it is mastered by the brain. Progress in Neurobiology, 156, 164–188. CC BY 4.0.

Digital environments create chronic low-grade stress. The constant stream of notifications, the ambient anxiety of social comparison, the fragmented attention, the disrupted sleep from screen exposure—all of this places the body under continuous allostatic load.

The feedback loop operates like this: as the body loses coherence, the steward’s capacity weakens. Anxiety and depression are not just psychological—they’re the predictive machinery breaking down. When you’re depressed, relevance realisation fails. Nothing seems to matter. You lose the capacity to grasp what’s salient for your own maintenance. The steward is dissolving.

5.3 The Polyvagal Mechanism: Why Threat Breaks Stewardship

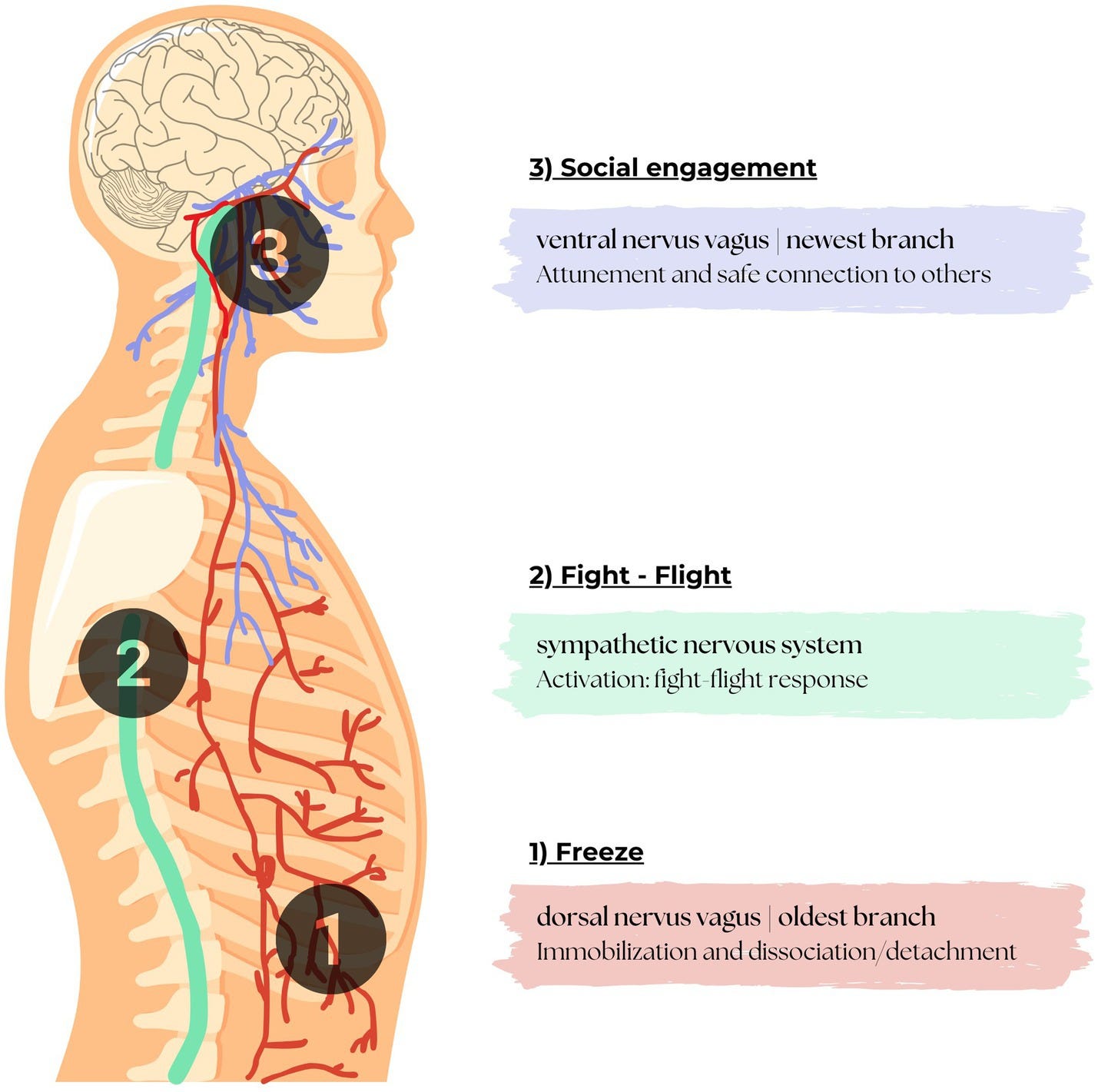

Stephen Porges’s polyvagal theory provides the physiological mechanism for how disruption breaks stewardship. Your nervous system operates on a three-level hierarchy:

1. Ventral Vagal (Social Engagement): Safe, connected, open. You can think clearly, relate authentically, care for yourself and others. This is where stewardship is possible.

2. Sympathetic (Fight/Flight): Threat detected. Resources redirect to immediate survival. Long-term maintenance shuts down. Who cares about hygiene when you’re running from a tiger?

3. Dorsal Vagal (Shutdown): Overwhelm. Freeze, collapse, dissociation. All maintenance ceases. This is depression’s physiological signature.

Figure 8. The three polyvagal states and their anatomical pathways. The dorsal vagal branch (oldest) provides immobilisation/shutdown in danger; the sympathetic system drives fight-or-flight mobilisation; the ventral vagal branch (newest) activates safe social connection and co-regulation. When the nervous system detects threat, it shifts down this hierarchy, making long-term self-care neurologically impossible. (Haeyen, 2024; based on Porges, 2011)

Source: Haeyen, S. (2024). A theoretical exploration of polyvagal theory in creative arts and psychomotor therapies for emotion regulation in stress and trauma. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1382007. CC BY 4.0.

Table 7. Polyvagal States and Their Impact on Stewardship Capacity

Note. Based on Porges (2011). Modern environments often keep people chronically in sympathetic or dorsal vagal states, making stewardship neurologically impossible. Stewardship practices signal safety and help return to ventral vagal.

Here’s the problem: modern environments keep you chronically in threat states. Not acute danger (tiger), but ambient threat (notifications, deadlines, comparison, isolation). You’re stuck in sympathetic activation or dorsal shutdown. And in those states, stewardship is neurologically impossible.

You cannot care for your body when your nervous system believes you’re under threat. The capacity for long-term thinking, self-reflection, and maintenance behaviours requires ventral vagal activation—the state of safety. This is why people in chronic stress stop showering, stop cooking, stop reaching out. It’s not laziness. It’s nervous system state.

The stewardship practices (sleep, movement, hygiene, connection) don’t just maintain the body—they signal safety to the nervous system. They shift you back into ventral vagal, where stewardship becomes possible again. This is the feedback loop: safety enables care, care reinforces safety.

5.4 The Social Dimension—Dunbar’s Number and Junk Connections

This isn’t just individual psychology—there’s a social dimension to this disruption.

Robin Dunbar’s research on primate grooming behaviour led to what’s now called Dunbar’s Number: humans can maintain approximately 150 stable social relationships. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s a function of our brain architecture and the amount of time required to maintain bonds through social grooming.

In primate societies, grooming serves a critical function beyond hygiene. It’s how bonds are maintained, coalitions are formed, social coherence is created. Grooming is embodied relationship maintenance. Critically, grooming creates the trust and attunement necessary for something more profound: moments where the group becomes a single coherent unit—what psychologist Keith Sawyer terms “group flow” or “social flow.”

Digital platforms promise to expand our social capacity infinitely. But they do the opposite—they flood us with what we might call junk connections: parasocial relationships, weak ties, anonymous interactions that carry none of the coherence-building properties of embodied grooming. These interactions are too shallow, too frictionless, to generate the depth required for social flow. We’re socially overstimulated but emotionally starved—starved specifically of the possibility of becoming a “we.”

The result is what’s been termed the loneliness epidemic. Recent data supports this: the 2023 WHO Commission on Social Connection found that social isolation carries mortality risks equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes daily. In the United States, over 50% of adults report feeling lonely (U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory, 2023). Importantly, this loneliness correlates strongly with increased social media use—not causally simple, but suggestive of the “junk connection” hypothesis. We’re more “connected” than ever but more isolated.

Figure 9. The loneliness epidemic in numbers. Social isolation carries mortality risks equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes daily. Digital platforms flood us with weak ties while starving us of the deep connection our biology requires. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023)

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community.

Because connection without embodied presence, without the reciprocal grooming practices that build trust and enable social flow, is not true relationship—it’s simulation.

Figure 10. Social isolation activates neural craving responses similar to hunger. The brain treats social deprivation as a survival threat, demonstrating that connection is not optional but a biological necessity. (Tomova et al., 2020)

Source: Tomova, L., Wang, K. L., Thompson, T., Matthews, G. A., Takahashi, A., Tye, K. M., & Saxe, R. (2020). Acute social isolation evokes midbrain craving responses similar to hunger. Nature Neuroscience, 23(12), 1597–1605.

Important caveat: Not all digital interaction is extractive. Video calls enabling elderly care coordination, online support groups for rare conditions, long-distance relationships maintained through thoughtful communication—these can foster genuine coherence. The distinction is between connections that supplement embodied relationships versus those that replace them entirely, and between interactions designed for human flourishing versus those optimised for engagement metrics.

5.5 The Predictable Consequences

Put it all together:

• Hijacked relevance realisation (attention captured by engineered surprise)

• Chronic allostatic load (body under sustained stress)

• Fragmented sleep (circadian rhythms disrupted by screens)

• Social isolation (junk connections replacing embodied bonds)

• Sedentary lifestyle (bodies designed for movement kept stationary)

• Processed food (nutrient-poor, disrupting gut-brain signalling)

• Threat state activation (nervous system chronically defensive)

Table 8. The Dissonance Engine: Factors Disrupting Modern Stewardship

Note. These factors operate synergistically, creating a systematic assault on bodily coherence.

This is a systematic assault on every aspect of bodily coherence. And the consequences are exactly what the ERE model would predict: soaring rates of anxiety and depression (Twenge et al., 2019; Weinberger et al., 2018), chronic fatigue, metabolic dysfunction, autoimmune conditions, and a pervasive sense of meaninglessness.

These are not separate epidemics. They are manifestations of the same underlying disruption: the body-steward feedback loop has been broken. The Great Un-Grooming has left us with bodies we can no longer adequately steward and stewards who can no longer maintain coherence.

As the biblical wisdom states: “Each day has enough trouble of its own” (Matthew 6:34). We are equipped to handle today’s trouble—but only if we handle it today. The trap is accumulation. Skip today’s hygiene, and tomorrow you have two day’s worth. Ignore today’s conflict, and next week you have a crisis. Let small neglects compound, and eventually you’re buried under decades of unresolved trouble.

Part VI: The Solution—Reclaiming Stewardship Through Ancient Technologies

6.1 The Intuitive Exodus

At the same time, something else is happening. Across demographics and ideologies, people are fleeing. Not physically, but practically—towards what they intuitively recognise as coherence-building practices.

The return to church and ritual. The explosion of interest in homesteading and craft. The rediscovery of cooking, gardening, making things with hands. The turn towards community, towards face-to-face gathering, towards practices that require embodied presence.

This is not nostalgia. This is the organism’s rebellion. It’s an intuitive recognition that something has been lost and must be recovered. People are rediscovering, without always having the language for it, the technologies of stewardship.

6.2 Hygiene as Fore-Giving: The Anticipatory Logic of Care

How do we fight dissonance and cultivate coherence? The answer is not a “top-down” app or idea. The “Dissonance Engine” cannot be defeated on its own disembodied terms. The rebellion must be “bottom-up.”

The primary technologies of this rebellion are hygiene, grooming, diet, and exercise. But we must reframe them entirely.

These are not mundane chores; they are the operational technologies of fore-giving—anticipatory care that happens before crisis.

Fore-giving is fundamentally different from forgiving (retrospective pardon). Fore-giving is when the giving happens before it is needed. You don’t wait until your teeth rot to brush them. You don’t wait until you collapse to rest. You don’t wait until loneliness crushes you to reach out. You give your body what it needs before it suffers the consequences of neglect.

This is anticipatory love. It’s recognising that this body, this vehicle for consciousness, deserves to be cared for before it breaks. Each practice is laying down structure for the self you’re becoming. You’re not just maintaining what is—you’re constructing what could be. You’re giving body to spirit, building the substrate that a vibrant self can inhabit.

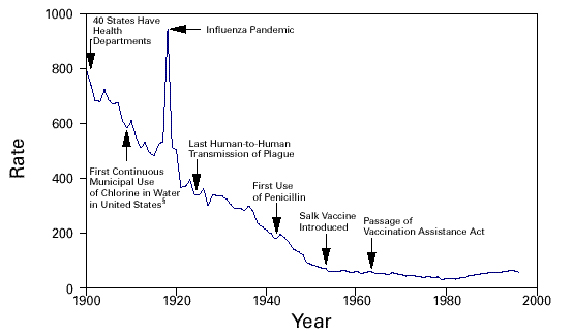

6.3 The Historical Evidence

Historically, the evidence is overwhelming: improvements in hygiene have been the single greatest driver of increased human lifespan and health. Thomas McKeown’s research demonstrated that declining mortality in the 20th century came primarily not from medical advances but from public health improvements—clean water, sanitation, food safety. Cutler and Miller (2005) found that clean water alone added approximately 15 years to life expectancy in the United States.

Figure 11. Hygiene transformed human health. Clean water, sanitation, and basic hygiene practices added decades to human lifespan—not through medical intervention but through anticipatory care that prevents disease before it starts. (Cutler & Miller, 2005)

Source: Cutler, D., & Miller, G. (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth-century United States. Demography, 42(1), 1–22.

Dental hygiene provides a clear example. Without regular brushing and flossing, bacteria accumulate, leading to decay, gum disease, and eventually tooth loss. But the consequences don’t stop in the mouth—oral bacteria are linked to cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, and systemic inflammation (Sheiham, 2005).

Figure 12. Oral hygiene demonstrates the cascade effects of maintenance. Neglected dental care leads not just to tooth decay but to systemic inflammation and disease, showing how small neglects compound into system-wide dysfunction. (Sheiham, 2005)

Source: Sheiham, A. (2005). Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(9), 644.

The failure to maintain one small aspect of bodily coherence cascades into systemic dysfunction.

Or consider menstrual hygiene. The development of modern menstrual products fundamentally changed women’s capacity to participate in public and professional life (Freidenfelds, 2009). This wasn’t just about comfort—it was about enabling sustained engagement in contexts that were previously inaccessible during menstruation.

Food preparation—making food safe and digestible—is itself a form of hygiene. Richard Wrangham argues in Catching Fire that cooking may have been essential to human brain evolution. By pre-digesting food through heat, we made more calories available for brain development. (Note: Wrangham’s hypothesis remains debated, but the broader point holds: food preparation practices that make nutrients more bioavailable represent coherence maintenance technologies.) Cooking is coherence technology.

Figure 13. Ancient Egyptian hygiene artefacts. Hygiene practices are not modern inventions but ancient technologies of coherence—ways that humans have always maintained bodily integrity through anticipatory care. (Glencairn Museum, 2019)

Source: Glencairn Museum. (2019). Daily life in Ancient Egypt: Insights from the Glencairn Museum collection.

6.4 The Goldilocks Zone: Between Neglect and Obsession

Here’s the nuance: stewardship is not about maximisation. It’s about optimisation. There’s a Goldilocks zone of care.

Too little maintenance leads to decay, illness, depression—the body loses coherence, and the steward begins to dissolve.

Too much maintenance can also be pathological. Obsessive hygiene—constant cleaning, ritualistic washing, hypervigilance about contamination—is itself a form of lost coherence. It represents relevance realisation gone wrong, where the steward treats the body as enemy rather than partner.

The optimal zone is what we might call appropriate care—maintenance practices that preserve coherence without becoming pathological. The serenity prayer captures the steward’s core challenge: knowing what must be changed, what must be accepted, and having the wisdom to distinguish between them.

Some aspects of your body cannot be changed—chronic conditions, disabilities, genetic limitations. These must be accepted. Fighting them wastes energy better spent elsewhere. Other aspects can be changed—sleep habits, nutrition, movement patterns. These must be altered. Accepting them as inevitable wastes the agency you have.

The art of stewardship is loving wisely—meeting reality where it is, not where you wish it to be, while still working towards what could be better.

Table 9. The Coherence Spectrum: Finding the Goldilocks Zone

Note. Both too little AND too much “care” can be pathological. Optimal coherence is context-dependent and varies by individual circumstances.

Stewardship is not about achieving perfect control. It’s about maintaining sufficient coherence for your particular body and life circumstances. This varies by:

• Biological capacity (chronic illness, disability, neurodivergence)

• Life context (caregiving demands, resources, systemic constraints)

• Developmental stage (infant, child, adult, elderly)

• Temporary circumstances (acute stress, illness, major life change)

Stewardship Across Different Bodies

The ERE model illuminates something crucial: stewardship is always particular. You are not stewarding an abstract body—you are stewarding this body, with its specific capacities, rhythms, and requirements. This is where the model becomes most powerful for those whose bodies diverge from statistical norms.

Chronic pain conditions reveal stewardship at its most sophisticated. When the body’s signals are amplified or unreliable, the steward’s task shifts from simple signal-following to signal-interpretation. You learn which pain signals demand immediate response and which are noise in a sensitised system. This isn’t a failure of interoception—it’s interoception operating in a different register, requiring a more nuanced dialogue between steward and body. The practice becomes: What is this signal actually telling me? What response will maintain coherence rather than trigger further dysregulation?

Executive function differences (ADHD, autism, brain injury) demonstrate that predictive machinery comes in different configurations—not deficient, but distinct. The autistic steward may find that routine and predictability aren’t rigidity but the very infrastructure of coherence. The ADHD steward may discover that novelty and movement aren’t distractions but essential inputs their particular system requires. Stewardship here means learning your brain’s actual operating parameters rather than forcing it into neurotypical patterns. The body-steward relationship remains—only the specific practices differ.

Chronic illness (autoimmune conditions, ME/CFS) teaches us that rest is stewardship. When energy is the scarce resource, the steward’s highest skill becomes conservation and strategic deployment. Choosing to rest before collapse isn’t giving up—it’s the most sophisticated form of anticipatory care. These conditions reveal what the model has always implied: coherence is not about doing more but about matching action to actual capacity. For some bodies, stillness builds more coherence than movement ever could.

Mental illness with biological components shows stewardship working through medical intervention, not despite it. When neurochemistry impairs the steward’s capacity to steward, medication that restores that capacity is a stewardship practice—no different in principle from feeding a hungry body or resting a tired one. The depressed brain struggling to find anything relevant is not a moral failure; it’s a system requiring support to return to baseline function. Seeking that support—therapy, medication, hospitalisation if needed—represents the steward using every available tool to maintain the body that maintains it.

The deeper insight: stewardship is not about achieving some universal standard of wellness. It’s about sustainable coherence for your particular embodiment. The goal is not to steward your body into resembling someone else’s—it’s to learn what your body-steward system needs to remain in dynamic stability.

Communal stewardship emerges naturally from this understanding. When individual capacity is limited—whether temporarily or permanently—others can hold parts of the stewardship function. This isn’t dependency as failure; it’s the ancient human pattern the model predicts. We evolved as interdependent beings precisely because stewardship was never meant to be carried alone. The parent stewarding the infant, the community supporting the ill, the friend checking in during crisis—these are stewardship distributed across multiple bodies, coherence maintained collectively when it cannot be maintained individually.

This is the model’s most radical implication: your body is worth stewarding exactly as it is. Not the body you wish you had. Not the body you’re told you should have. The one you’re actually in, with all its particularities, limitations, and specific requirements. That body generated you. That body needs you. And learning its particular language—however different from the statistical norm—is the work.

6.5 The Developmental Trajectory of Stewardship

Stewardship is not innate—it’s learned. And there’s a clear developmental trajectory through which we become competent stewards of our own bodies.

Stage 1: Co-Regulation

The infant cannot steward itself. The caregiver provides external stewardship—feeding, cleaning, soothing. Daniel Stern’s work on infant-caregiver dyads shows that the self begins in relationship. The baby learns bodily coherence through the regulated attention of the caregiver. This is co-regulation—the stewardship function performed by another until the child can internalise it.

Stage 2: Exploration

The child’s exploratory play is itself a form of proto-stewardship. Alison Gopnik describes children as “little scientists,” testing hypotheses about how the world works. This is the child learning to predict and respond—learning how to navigate context. Play is practice for stewardship.

Stage 3: Autonomy

The critical developmental milestone is when the child begins taking over their own bodily maintenance. Toilet training is not just about social propriety—it’s the child’s first act of autonomous stewardship. They learn to recognise their body’s signals (interoception), predict needs, and respond appropriately. This solidifies what Philip Zelazo and Ulrich Müller call the “executive self”—the capacity to coordinate one’s own behaviour towards goals.

Stage 4: Refinement

The adolescent and adult optimise stewardship practices through conscious attention and relevance realisation. This is where the four ways of knowing become explicit: learning about health (propositional), practising habits (procedural), joining communities of practice (perspectival), and making it identity (participatory).

Table 10. Developmental Trajectory of Stewardship Capacity

Note. Stewardship is a learned skill that develops through these stages. Disruption at any stage can impair adult stewardship capacity.

This developmental sequence reveals something important: stewardship is a skill. It must be learned, practised, cultivated. And critically, it can be disrupted. When development is interrupted—through trauma, neglect, or environmental chaos—the capacity for stewardship can be impaired.

6.6 The Practice Protocol: Embodied Stewardship in Daily Life

Theory without practice is philosophy. Practice without theory is superstition. What follows is a practical protocol for daily stewardship—grounded in the ERE framework but immediately actionable.

This is not a productivity system. This is a maintenance protocol. The goal is not optimisation—it’s coherence.

Table 11. The Embodied Stewardship Practice Protocol: Summary

Note. Start with 1-2 practices that resonate most. The goal is sustainability, not heroic effort.

The following sections elaborate on each practice in detail.

6.6.1 Morning Stewardship (10-15 minutes)

Morning practice sets your baseline for the day. Beginning with coherence builds reserve capacity that carries you through challenges.

Practice 1: Interoceptive Check-In (3 minutes)

Before reaching for your phone, before getting out of bed, take 3 minutes to scan your body:

• How does the body feel right now? Heavy? Light? Tense? Relaxed?

• What sensations are present? Pain anywhere? Stiffness? Comfort?

• What is the quality of your energy? Full tank? Half full? Running on empty?

This isn’t meditation—it’s data collection. You’re reading the dashboard before driving. Research shows that interoceptive awareness—the ability to accurately perceive internal bodily states—predicts better emotion regulation, decision-making, and stress resilience (Farb et al., 2015).

Practice 2: Hydration Before Stimulation